Next month, on 11 September, a report to York Region’s new Housing and Homelessness Committee will paint a picture of homeless people who were living in the Region late last year.

This “point-in-time” survey captures the characteristics of the homeless in a single 24-hour period in November 2024. As with previous counts (2016, 2018 and 2021) the survey was voluntary. And though the numbers participating were modest, the responses will still give us valuable insights. Who are the homeless? Are they from York Region or are they moving here from other places? What is their average age, ethnicity, gender and previous or current occupation? Are they single or do they have a partner? How many have mental health issues? How did they fall into homelessness in the first place?

These are intrusive questions but we need to know.

The last count in 2021 took place during the Covid pandemic which clearly impacted the number of responses. The count found 329 people were homeless in York Region (a molecular fraction of the Region's 1.25 million population). Of these 53% self-identified as chronically homeless – that is, homeless for longer than 6 months in the past year. (Photo right: at Davis Drive and George Street. 29 June 2025)

Surge in homelessness

By 2024 Regional officials were reporting that 2,525 people were known to have experienced homelessness – a 35% increase from 2023.

“Chronic homelessness more than doubled with 986 people accessing homelessness services. Despite funding nine emergency and transitional housing programs with 293 year-round beds, demand continues to exceed available capacity.”

We are not alone. In June, Toronto’s homeless population – estimated at 15,400 – was described as being at “crisis level” with the number doubling in three years. But these figures – though shocking and alarming – probably represent the tip of the iceberg.

Invisible

To most people the homeless are largely invisible. So they are not given a second thought.

But the moment we start seeing them, our perception changes overnight.

Visible homelessness is a relatively new phenomenon in Newmarket, generally seen as a well-off Town which regularly receives accolades celebrating its liveability. But times change.

The Chair of the Housing and Homelessness Committee, Newmarket Mayor John Taylor, has been warning for years of an exponential growth in people experiencing homelessness.

Noticeable increase

In 2022 Taylor told Newmarket Today the rise in homelessness was noticeable.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that we just experienced a summer with the highest level of homelessness in our community.”

And in March 2024, he warned:

“This issue with people experiencing homelessness in our communities is going to hit us extremely quickly and hard… We all know in a few years we're going to have significant encampments if we don't get ahead of this.”

Neighbour in a Tent

The Mayor's predictions didn't take long to materialise. Last winter, for the first time, I noticed a tent pitched alongside the boulevard in Kingston Road, a ten minute walk from where I live. The tent appeared with all the usual baggage, the shopping cart overflowing with tattered belongings.

Some street people live that way because they want to – and there are no mental health issues clouding their judgement. But the overwhelming number of homeless people end up there because they don’t have enough money to put a roof over their head. (Photo right: Outside Newmarket public Library)

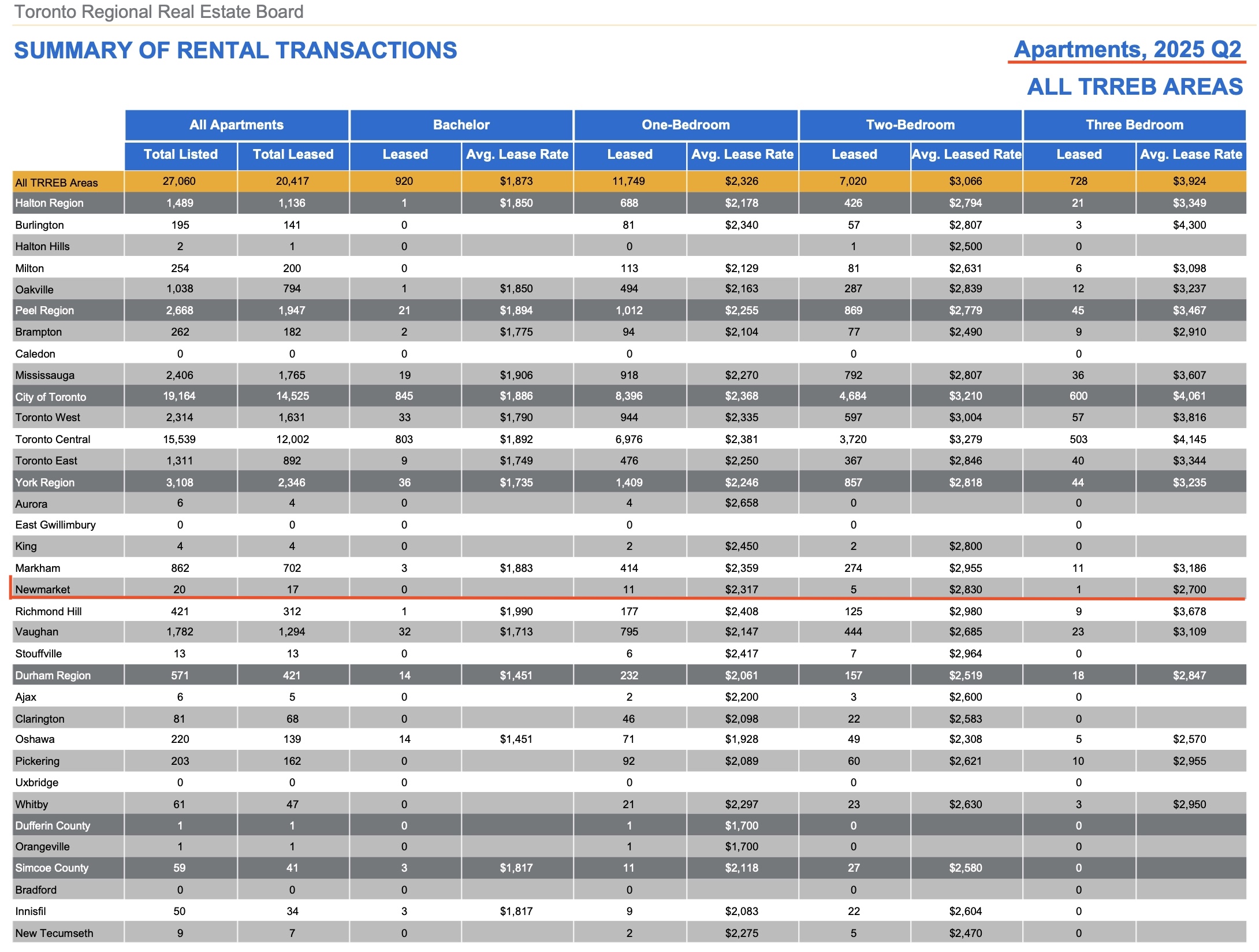

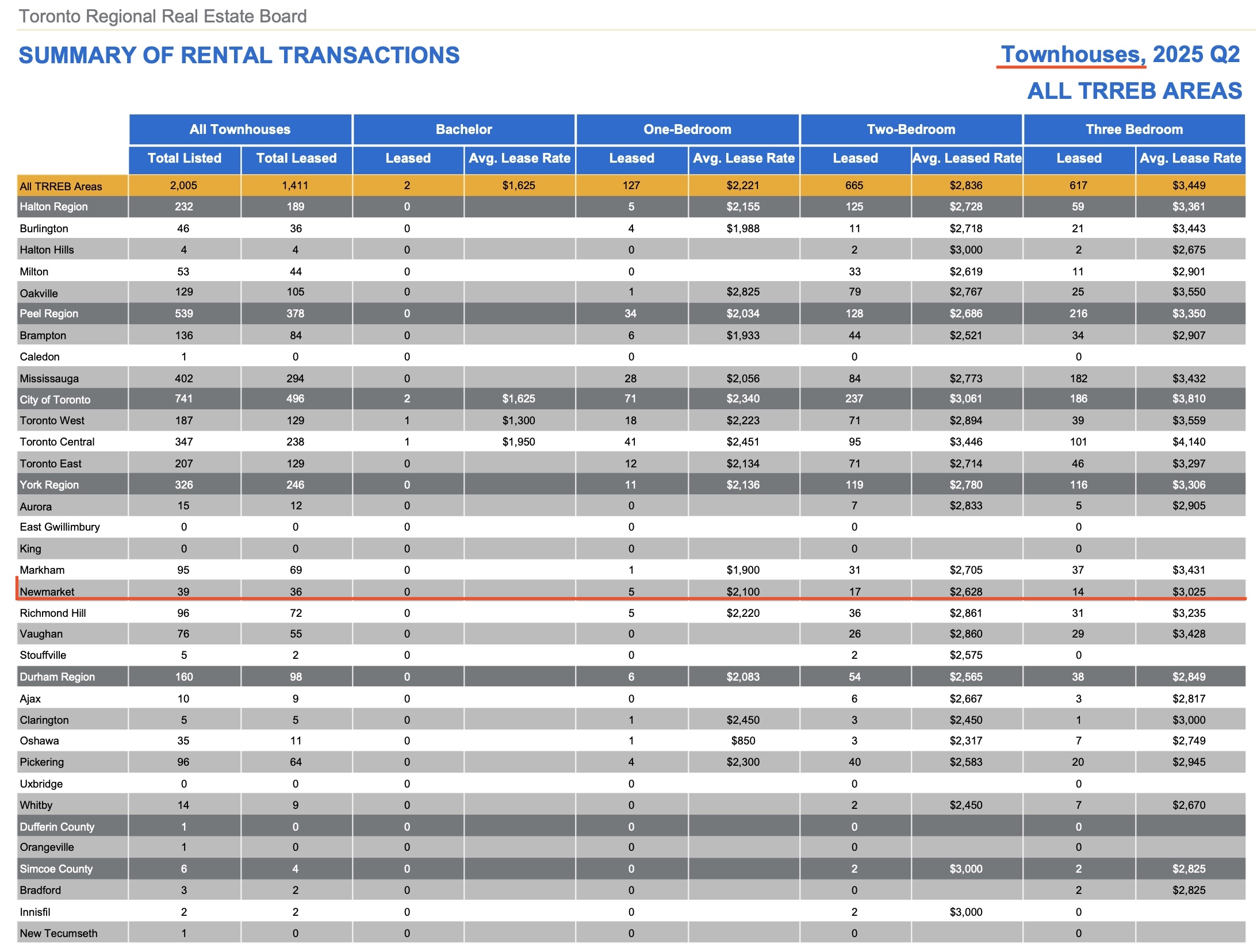

The latest quarterly figures for Newmarket from the Toronto Region Real Estate Board show a miniscule number of rental properties offered at daunting rents. Other non TRREB realtors work in Town but their figures, I suspect, are likely to mirror those from the TRREB which represents the overwhelming majority of realtors. (see tables below)

Eye-watering

A one-bedroom apartment is rented at $2,317 pm or $27,804 annually. At York Region’s own affordability guidelines (which recommends that no more than 30% of gross income should go on housing) this would imply a renter with a gross income of at least $92,680. Who knows?

In 2021, about 13% of York Region households (47,850 low-and-moderate income households including over 18,000 renter households) were in “core housing need”. This includes households that spend 30% or more on housing costs and live in inadequate housing.

Housing affordability crisis

York Region is one of the fastest growing regions in Canada with house prices increasingly beyond the reach of those even on above average incomes. The Region has been wrestling with the housing affordability crisis for years.

We live in an attractive Town in one of the wealthiest regions of a rich country. So how on earth did it come to this?

York Region’s recently retired Commissioner of Community and Health Services, Katherine Chislett, put it this way on 7 March 2024.

“We are doing a lot of really excellent work but it really is a drop in the bucket. We've been in this situation now for a good three decades. We’ve seen it coming. (There was) the cessation of some very, very significant federally and provincially funded construction programs for social housing that were ended in the 1990's. The end of rent controls on buildings. The locking in of social assistance rates which are well below the poverty line. We’ve had an increase of 25% year over year in the number of people on Ontario Works so it is an issue… We are looking at a continued steady and very rapid growth (of homelessness) in this Region.”

What needs to be done

We know what needs to be done. Katherine Chislett has just reminded us.

Municipalities need to start building social housing again, rapidly and at scale. The private sector on its own is not willing to do this.

This is not just the bleating of lefty liberals. Conservatives like Richmond Hill's Joe DiPaolo say as much.

We also need to revisit social assistance rates to give people the support they need when they need it most.

And don't tell me there isn't any money.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Update on 17 August 2025: The Barrie Encampment

Note: York Region’s 2021 homeless count

“York Region’s 2021 homeless count was conducted June 1 and 2, 2021. As part of the Point-in-Time (PiT) count, homelessness services sector staff across York Region conducted a count and voluntary survey of people in emergency housing (shelters), COVID-19 transitional shelters, Violence Against Women (VAW) shelters, transitional housing, substance use beds, and people living outdoors. A PiT count provides a snapshot of people experiencing homelessness over a single 24-hour period. It focuses on people staying in sheltered and unsheltered conditions.

“Over half (53%) of respondents reported experiencing long term or chronic homelessness, up from 45% in 2018 and 33% in 2016. Eighty-two percent (82%) of people experiencing long-term or chronic homelessness were single or did not have other family members staying with them on the night of the count and 60% were men. This is similar to 2018 when 84% were single or had no family members staying with them that night and 63% were men. People experiencing chronic homelessness were more likely to report multiple health issues (70%) than respondents who were not experiencing chronic homelessness (59%).

“Count 2021 identified 238 people (72%) staying in an emergency housing (shelter) or shelter for Violence Against Women, 17 people (5%) who were unsheltered (including sleeping outdoors, places not designed for human habitation, and encampments), and 74 (23%) who were provisionally accommodated. In York Region, like many communities, most experiences of homelessness are hidden. People living temporarily with others (hidden), who have largely not been counted through I Count 2021, are likely the largest group of people experiencing homelessness in York Region. Estimates suggest that up to 80% of homelessness is hidden in Canada.

“Count numbers should be considered the minimum number of people experiencing homelessness in York Region. The percentage of people who were both staying in emergency housing (shelters) and experiencing chronic homelessness (51%) increased substantially since 2018, when it was 35%.

“More people living unsheltered and in provisional accommodations reported having substance use issues, mental health issues, physical limitations, and cognitive or intellectual limitations than people staying in emergency housing. This is consistent with findings from 2018.